Venture capital investing is popularly construed to be the exclusive province of institutions and wealthy individuals who invest in private offerings. Some define it more granularly, as an investment by a VC fund, and call investments before that “seed capital.” I’ve seen references to “pre-seed capital,” which refers to capital provided before that.

The apparent reason for such distinctions may be the idea that an investment by a VC firm “legitimizes” a startup. I think it has more to do with valuation—until a “Big Dog” establishes one, no one really knows where to set it. The fact is that no one knows how to reliably set a valuation for a startup, but that’s a different matter. The question I focus on here is “Is venture capital raised in initial public offerings?”

Recently, I spoke at the Global Capital Summit put on by F50 at Stanford University, which focused on the changing nature of venture capital.

Speakers reported that companies were raising larger amounts of money at a given stage than before.

Also, that VC funds were increasingly investing after a company was generating revenue—so angel investors are providing a larger proportion of funding for startups that are at a pre-revenue stage.

These developments inspired observations like “pre-seed is the new seed” and “series A is the new series B.” No one said that investments made by angels wasn’t “venture capital,” but I’ve heard it suggested elsewhere.

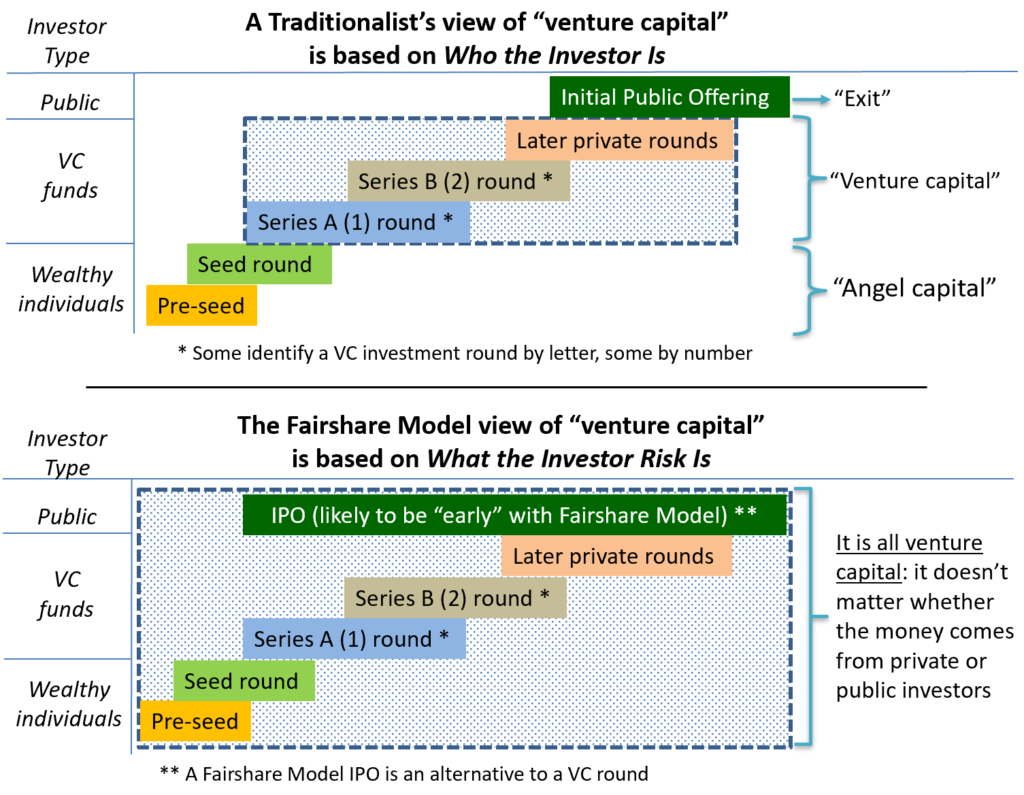

One thing that hasn’t changed is the view—in Silicon Valley, on Wall Street, and elsewhere—that an IPO does not constitute another raise of venture capital. Indeed, an IPO is commonly seen as an “exit”—a way for pre-IPO investors to liquidate their position by selling shares in the secondary market to public investors.

To me, this traditional point of view is narrow. I define venture capital broadly—as an investment in a venture-stage company. A venture-stage company has these risk factors:

- Market for its products/services is new or uncertain.

- Unproven business model.

- Uncertain timeline to profitable operations.

- Negative cash flow from operations; which means it requires new money from investors to sustain itself.

- It expects to continue to have negative cash flow from operations; its future depends on its ability to raise more money later.

- Little or no sustainable competitive advantage.

- Execution risk; the team may not build value for investors.

These characteristics sound familiar, don’t they?

That’s because they routinely appear as risk factors in IPO prospectuses.

A foundational concept for the Fairshare Model is that capital provided to a venture-stage company is venture capital regardless of its source; it doesn’t matter if it is supplied by wealthy or average investors. Ergo, it doesn’t matter whether the money is raised in a private or public offering.

Put another way, whether or not an investment is venture capital ought to be a question of “What”, not “Who.” That is, the question should be decided based on whether a company presents venture-stage risks, not by who invests.

The difference between these two views of venture capital is depicted below.

One could argue that this diagram should include investors who invest in a venture-stage company in the secondary market. It doesn’t because they buy stock from existing shareholders, not from the company itself. To me, a venture capital investor provides capital directly to a venture-stage company.

The Big Idea behind the Fairshare Model is to adapt the ideas behind a modified conventional capital structure—the VC Model—to an IPO. [The three types of capital structures for equity are described in articles listed below.]

Without price protection, the financial returns posted by VC and private equity funds over past decades would not have been as impressive as they have been. By adapting the price protection concept to venture-stage IPOs, the Fairshare Model reduces valuation risk for public investors. That makes it more likely that they will make money when they invest in a company with high failure risk.

Making it more attractive for public investors to invest in companies with high failure risk is not as crazy as it sounds. Since the 1980’s, venture-stage companies have contributed more to economic growth and job creation than those who were in the Fortune 500.